Fieldwork adventures of a British linguist

Tuesday, February 1, 2022

from the 1960s.

During the 1960s, the Oxford linguist Tony (Antony) Hurren and his wife visited the Istro-Romanian villages of the Istrian Peninsula, in Croatia. Fifty years later, his widow, Mrs Vera Hurren, generously made a gift to Oxford University of a large amount of unpublished material connected with the linguistic research her husband conducted there. Vera Hurren’s donation was the starting point of our ISTROX project.

In the spring of 2019, we travelled to Istria to meet former participants (or in some cases the surviving relatives) in Tony Hurren’s research, to obtain their permission to use the material donated by Mrs. Hurren for our research and make it public. The first reaction that Adrijana Baćac had as we met her in front of her house in Šušnjevica and mentioned Tony Hurren’s name, was to exclaim with a smile: “Toni and Vera, Hampton Poyle!”. Adrijana, who had been interviewed by Tony Hurren when she was about 16, explained that she remembered “Hampton Poyle” (the name of village that has been the Hurren’s home) because, throughout the years, Vera kept in touch with her by sending letters, postcards, and small presents, particularly around Christmas. Looking back at Adrijana’s reaction during our field trip, we find it telling that she not only remembered the Hurren’s postal address in England, but also that she mentioned Vera Hurren’s name alongside that of her the husband she accompanied in the field for almost a decade.

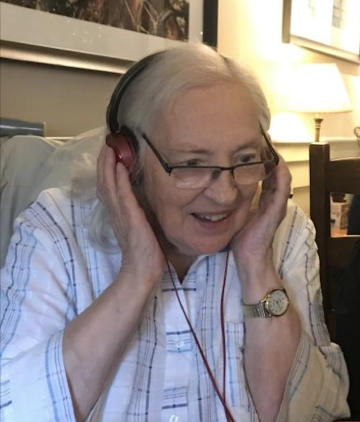

Vera Hurren belongs to a time when a woman’s dedicated assistance in the work of her male partner remained largely unacknowledged in academia. Today, as a way of showing our gratitude for the support that she offered to her husband throughout his work in Istria, and for the donation that has made Tony Hurren’s audio recordings available for future research, we have put together some of Vera’s reminiscences about their trips to Istria. We have met her several times in recent years, to learn more about her husband’s work and their experiences in Istria, and to keep her updated on developments in our project, which is aiming to expand the international conversation around the Istro-Romanian language and population.

We have edited our recordings of her for clarity and narrative purpose.

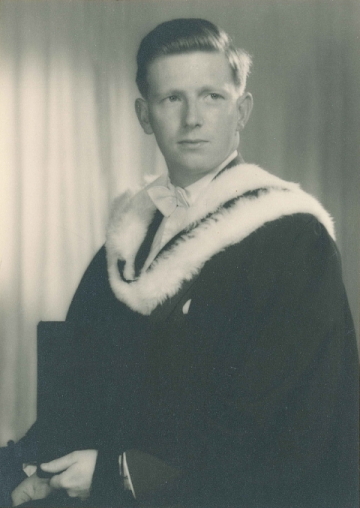

It was in 1963, I think, when we first went to the Istro-Romanian villages. I had moved to England at the end of the 1950s. I was born in East Germany, went to a Catholic school, but then I wanted to study something that would prepare me to support myself and allow me to move away from Germany and the Stasi, so I went to a commercial college to learn typing and book-keeping. I met Tony rather soon after I’d arrived in England, while working as a profesional secretary for the De La Rue company. We got married in the summer of 1962, and straight after our marriage ceremony we moved in this house in Hampton Poyle, which has been our home ever since. After we got married, Tony went straight back to Oxford University, where he had studied Modern Languages, French and Italian, and he started a research project to read for a doctorate. His chosen subject was Istro-Romanian, which I understood to be spoken by a few hundred people in what was at the time Yugoslavia. This is how he started travelling to the Istrian peninsula, where there were several villages inhabited by the people who spoke this language. I accompanied him each summer between 1963 and 1970.

I loved travelling with Tony for his research. There’s a somewhat funny side to this travelling of ours… I mean, for almost a decade, I was unable to keep a steady job or advance in my career as I kept changing jobs every year: I would spend nine months in a job with a company, then I would resign at the beginning of the summer to go away with Tony for three months. I would then return sometime in the autumn, look for another job and do the exact same thing the following spring. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, I worked for various companies in Oxfordshire, then I taught German in a school – which was better than most as it gave me a three-month summer holiday anyway… We kept going to Istria every summer until the beginning of the 1970s, when Tony was invited to teach Linguistics in America for a year, so we went together to the University of Florida in Gainesville. We travelled to America by boat, it took quite a while to get there. I took with me my German typewriter, supposedly a portable one, but as heavy as cement, so I could type out Tony’s work. I typed all the work that he produced over the years, including his doctoral thesis, which he submitted in 1972. Can you imagine what it means to type an entire thesis in linguistics, about a language that you do not understand and that needs so many special symbols to write it down? And remember that I was working on a typewriter and not on a computer: every time Tony discovered a mistake, I had to re-type the whole page! Yet, I still enjoyed doing it: he was so passionate about his work… At the end of one of these summers, as we returned from Istria, we stopped in Paris, where we had our car burgled. Among the stolen goods were some of the recordings that he had made of speakers of Istro-Romanian. Tony was devastated at the time, but then he found the strength to start all over the next summer… His research on this language was crucial for him. In 1971, at the end of our stay at the University of Florida, where he taught linguistics, he was offered the option to stay and start a research project on the Seminole Indians who lived in the region. He was genuinely interested and considered that option, but his mind was always on his research on the Istro-Romanians, so he wanted to return to Oxford and finish that and in the end, we left Florida after one year.

entrance to the church in Šušnjevica.

In 1963, when we first went to Istria, it was part of Communist Yugoslavia, so we had no idea what to expect when we arrived. Tony approached the situation very carefully. We started by going to the British Embassy, then to Zagreb University. He had with him official documents from Oxford University about his research project, just in case we were asked by the authorities to provide a reason for our being in the country. We really had no idea how we would be regarded by the Communist authorities… or by the villagers. In the end, it was not as bad as we had feared. Gradually, local people and even the authorities got used to us and we were able to move around quite freely. I was the one who organised the trips to Istria, and then the trips around the villages; I also drove the car – we had a Volkswagen that you can see in some of the pictures that I took. I loved to drive but I was not very good at finding my way, so Tony would have the maps and would often direct me when we were travelling, but it was me sitting at the wheel most times. I had this little Volkswagen from the day I took my driving licence, when I was about 21. Later on in our life together, we had several cars, all Volkswagens, in different colours: the first one was grey, then we had a blue one, then also a red one…

village of Kostrčan

Speaking of our first visit to Istria, I remember that there was one of the villagers – I cannot remember where from, but I know that he was neither from Žejane nor from Šušnjevica – who had a very close relation with the official authorities. People referred to him as “the Communist”. We understood that he used to go around the villages, try to learn things about people’s whereabouts… Naturally, he became interested in us and was somewhat suspicious when he first arrived to the village. Eventually we met him one evening at the pub, spent some time together, and then he became quite friendly with Tony. People usually got very fond of Tony once they got to know him. He was very funny, really a cheeky chap… It was also useful that Tony spoke several languages. The history of their country meant that the people in these villages used to speak various languages: the older ones spoke German, the middle-aged ones spoke Italian, which they had had to learn at school, and the younger ones spoke Croatian. By the time we got there, Serbo-Croat had become the official language of the country. I only spoke German, but Tony spoke both German and Italian, which helped a lot when we were there. Of course, the people communicated among themselves in their own languages [žejånski and vlåški, ed.], but could not write in those languages.

We always stayed in the same two places when we went to Istria. When we were in Šušnjevica, we stayed at the farmhouse owned by the Belulović family, Slavko and Dalla. This was one of the very few houses in the village where the family had no children, which means that there was room for us. Perhaps that was also the reason why their niece, Gracijela, was often there; her parents’ house was elsewhere in the village. I think she liked us: she was there most of the time. We also liked her very much. Tony interviewed her and two other teenage girls, plus another one who was younger… It was slightly difficult for Tony to work while we lived at the farm, as we had only one room which was rather dark. But the people were very nice, they would often come by in the evening to see how we were doing. When Tony was recording somebody in the courtyard, children would often surround him; he was always interested to listen to them. There were mostly women at home during the day, taking care of children, as men would, be away working in factories, mostly in Rijeka. Everybody worked very hard. Dalla Belulović, the woman who hosted us in the village, was one of the women who were more mobile at the time and sometimes travelled outside the village.

![1960s. Gracijela Bortul, Frane Stroligo [“Cattolico”], Tony Hurren at Pula Arena.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/pula-arena.jpg)

Tony Hurren at Pula Arena.

When we stayed in Šušnjevica we used to spend quite a lot of time with the niece of the Belulovićs and another man from the village… I cannot remember his name [we now think Vera is referring to Frane Stroligo], but I know that, in the village, he was known as “Cattolico” (‘Catholic’). He spoke German, so that both Tony and myself were able to talk to him freely. He was from Kostrčan, if I remember rightly… Sometimes we would take him and Gracijela for a trip outside the village. There was this Roman amphitheatre somewhere close to Šušnjevica, we sometimes went there on Sundays…

When in Žejane, we always stayed at the inn. The inn was somewhat larger than the house in Šušnjevica, brighter, and sometimes we had all of it to ourselves. The building was slightly raised from the ground, so that you could stand on the roof and observe the life of the village. I would often look at men playing ball games by the side of the pub. I can’t remember the name of the game, but I took some photos with them one year…

Life was difficult for most people in these villages. I remember that, at the end of our first summer there, before going back to England, I wanted to throw a small party for the people who had become closer to us. Nothing fancy, the times were hard, it was during Communism, there were food shortages and people could not afford much. I went to town and bought some things, made some sandwiches… Later that week, when we had the party, I suddenly realized how hard life was in the village, when somebody remarked that I had put butter on the sandwiches, and also added cheese, sausages… So I replied that yes, for us it was a very special party, a farewell party, so I wanted to have as many good things as I could find. I was happy to set up that party, but didn’t want anybody to feel embarrassed. And then, between that summer and the summer of 1970s, I organized a small farewell party at the end of each summer before leaving the village. But of course, our life out there was not about parties… Tony worked enormously hard when we were in Istria. He would talk to the people and record interviews during the day, then he would stay up most of the night. Once, when I tried to convince him to go to bed, he replied that he could not afford to do that, as he aimed to learn as many new words as he could each night. People said he had a wonderful memory and a sure gift for languages …

![1960s. Jože Doričić [“Dottore”] with Tony Hurren in front of Buffet Šija in Žejane.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/buffet-sija.jpg)

We kept in touch with some of the people for as long as we could. As Tony started publishing on the topic of Istro-Romanians, people who had roots in the region sometimes wrote to thank him or let him know things about themselves. I remember sometime after he had published something in a journal, he received a letter from somebody who was from one of these villages and was in America, and they started a correspondence that lasted for a while. Sometimes I would also send small presents to some of the villagers, in particular to the teenage girls that Tony had interviewed. For instance, I sent Gracijela a veil for her confirmation ceremony and sometime after that she sent us a photo with her wearing it.

Bortul and Dalla Belulović.

After Tony finished his thesis, he published part of his findings on Istro-Romanian and continued to teach it at Wadham College in Oxford University. Other than that, he took up a full-time position as head of the Department of Language Studies at Lanchester Polytechnic [now the University of Coventry]. It was not easy, as he had to commute four days a week to the Midlands, then teach in Oxford on Saturdays. Later on, in 1985, he became the Secretary of The Oxford Society (now the Oxford University Society, ed.) and, later on, became editor of the Oxford magazine published by the society. Apart from his research, Tony loved life, good wine and a good laugh (indeed, in his youth he had a reputation as a prankster … but that is another story). He died peacefully on 1 August 2006.

I am so glad that his research survives him and is still useful to other scholars who are researching the Istro-Romanian language today.

Hampton Poyle.

This material has been recorded and transcribed as part of ISTROX, a project developed in the Faculty of Linguistics, Philology, and Phonetics at the University of Oxford. ISTROX is based on a collection of sound recordings donated to the Taylor Institution Library in Oxford. Fifty years after these recordings were made by the Oxford linguist Tony Hurren, we combine linguistic research and online community-sourcing to explore the history of a severely endangered language: Istro-Romanian.

If you would like to learn more about our project, please click here.

If you speak or understand vlåški or žejånski and would like to take part in our project please contribute here or email us at istrox@ling-phil.ox.ac.uk

The original Hurren material is available in ORA (the Oxford Research Archive).